Groundbreaking Evidence From NAMES In The Gospels PLUS 4x1-Minute Cases On The Gospels As Eyewitness Accounts With Inspiring Philosophy

Does the use of names in the Gospels mirror what a fiction writer would produce? A groundbreaking peer-reviewed article helps answer the question

The Gospels: A window into eyewitness testimony

Find us on Medium.com

Or X

Or Insta:

instagram.com/streettheologianapologetics/

1. Evidence covered previously

2. Groundbreaking research paper comparing the use of names in the Gospels to fictional works, the apocryphal gospels and first century historians

3. Inspiring Philosophy’s 4x1-Minute Cases on the Gospels as eyewitness accounts

4. What this all means - Is the Jesus of the Gospels the Jesus of history?

Previously we have written on evidence that supports the Gospels are based on eyewitness accounts.

We looked at:

Manuscript and historical evidence shows consistent naming of the four Gospels

Undesigned coincidences

Historical precision

Names

Multiple attestation and multiple forms

Jesus’ favourite title for himself

The Gospels differ from early church wording/ issues so can’t be a direct result of it

Geographical precision

Unusual customs

Embarrassing details

Within the point on names, we looked at the research of Richard Bauckham as outlined below.

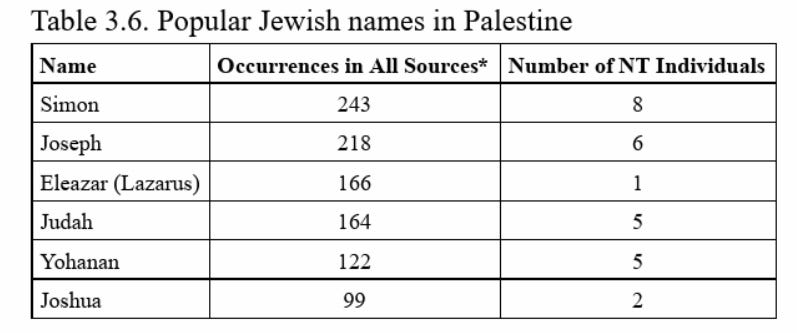

Bauckham has assessed the relative frequency of different personal Jewish names in Palestine. He investigated names from 330 BC to 200 AD with the bulk of the data coming from 50 BC to 135 AD. He excludes clearly fictional names. He has found “2953 occurrences of 521 names, comprising 2625 occurrences of 447 male names and 328 occurrences of 74 female names” (Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 71). Note his comparison of the most popular Jewish names in Palestine with the number of NT individuals.

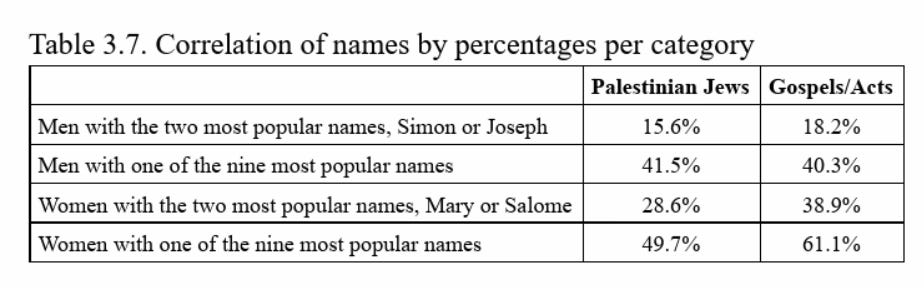

Bauckham also compared correlations of categories of names in Gospels/ Acts with what was found in Palestinian Jews and the numbers (particularly the male numbers) are reasonably similar.

JEWS FROM ELSEWHERE?

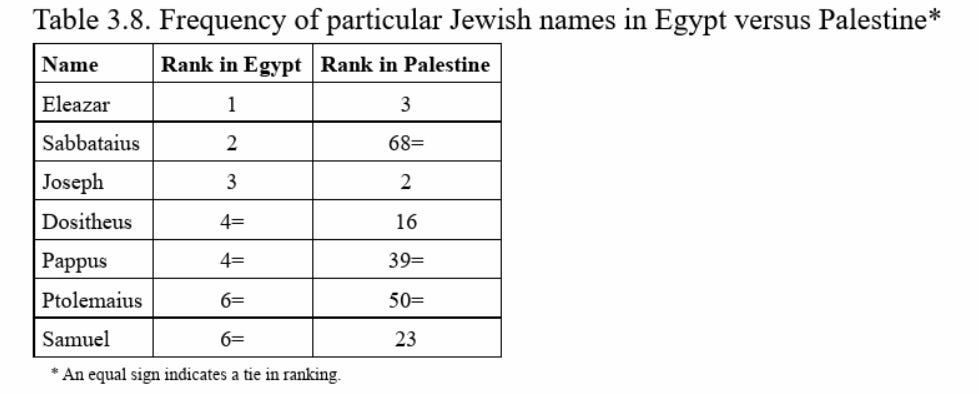

Perhaps Jews from somewhere else in the world knew what Jews are normally called and helped fabricate the Gospel names? Or maybe not... Jews in Egypt had different names from Jews in Palestine, as did Jews in Libya, western Turkey and most definitely Rome.

DISAMBIGUATION

Moreover, Bauckham highlights that the Gospels use disambiguation to distinguish between the more popular names. Common ways of removing ambiguity included adding a father’s name, a profession, or a place or origin.

For example, Simon Peter (Mark 3:16), Simon the Zealot (Mark 3:18), Simon the Leper (Mark 14:3) and Simon the Cyrenian (Mark 15:21). For Mary, we have Mary Magdalene and Mary, mother of James and Joseph.

APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS DON’T COMPARE

The apocryphal Gospels do a poor job by comparison. The Gospel of Thomas is the best of the worst and mentions James the Just, Jesus, Mary, Matthew, Salome, Simon Peter and Thomas. The Gospel of Mary mentions only five names: Andrew, Levi, Mary, Peter and the Saviour (not even Jesus by name- a clear later embellishment).

The Gospel of Judas mentions Judas and Jesus but introduces many names from the Greek literature and contemporary mysticism: Adam, Adamas, Adonaios, Barbelo, Eve = Zoe, Gabriel, Galila, Harmathoth, Michael, Nebro, Saklas, Seth, Sophia, Yaldabaoth and Yobel. (Source Williams Can we Trust the Gospels? 2018, p.69).

New Groundbreaking Research

However, in recent times, Luuk van de Weghe and Jason Wilson, in a peer-reviewed article, analysed the results of a goodness-of-fit test on names in the Gospels and Acts.

The results were astounding.

Van de Weghe and Wilson conclude:

The evidence suggests that the GA (Gospels and Acts) accurately retained personal names—those often unmemorable pieces of personal information—at a remarkably high level, reflecting characteristics more in line with Josephus than with ahistorical and novelistic samples. As Richard Bauckham notes: “All the evidence indicates the general authenticity of the personal names in the Gospels.”

Inspiring Philosophy’s Video on the Paper

Inspiring Philosophy’s Michael Jones produced a video on this paper and we discussed this video along with his case for the Gospels as eyewitness accounts with him.

Michael Jones explains in his video:

“To make a comparison to other samples, they also binned the names of persons from other texts in the same way and compared all these samples to the popularity statistics of the general population around the time of Jesus.

The other samples were the named persons from the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus, a random sample of Jewish names, a sample of all the named persons from non-canonical Gospels and similar material, and, last, the names from modern historical novels Ben-Hur and Louis de Wohl’s The Spear. This last category is important because it reflects what a forger might be able to create with access to names from the Gospels and Josephus. For example, de Wohl’s novel The Spear is a well-researched historical novel set around the time of Jesus, which incorporates many historical and fictional Palestinian Jewish characters. Lou Wallace, the author of Ben-Hur, claimed that he visited the Library of Congress and researched everything on the shelves relating to the Jews.

If the Gospels and Acts are more fiction than truth and were written by late forgers, the naming pattern in them should be similar to what we find in these historical novels.

Once the data was collected, van de Weghe and Wilson ran a goodness-of-fit test. This test takes all the popularity data from all the bins in a sample and then compares them to the percentages of the bins in the general population around the time of Jesus. It then considers, using an algorithm, the likelihood or probability that the sample in its entirety would occur if it were drawn from the general population. It then gives the whole sample a score—the P-value. P stands for probability. In other words, the P-value score tells us what the probability is that we would see a sample like this if it was from the general population around the time of Jesus.

The results were astonishing. They found all three fictional samples, including the historical novels, had an infinitesimally small chance of fitting in Jesus’s Palestine. In fact, the percentages were so small that they needed to be expressed with scientific notation. The names of Josephus obtained a P-value that rounded up to .07. In other words, if Josephus is historical, then there's a 7% chance his mix of male Jewish names would occur during the time of Jesus. This is a very low probability but still accepted by conventional standards. But the Gospels and Acts scored a P-value of .86, meaning if they are historical, then there's an 86% chance their mix of male Jewish names would occur during the time of Jesus.”

Confusing names with Jews outside of Palestine?

Michael Jones adds:

Additionally, the Gospels matched the names of Jews within Palestine and did not align with the names of the Jews living in the diaspora.

Not only did they get the ratio of names of the period correct, but they also managed to not mix them up with the popular names of Jews living outside of Palestine, while fiction writers could not even match with either set.

Therefore, the names in the Gospels are like an incredibly subtle watermark of authenticity—something no forger could recreate. They do not align with ancient fictional accounts nor with well-researched modern historical novels that copied many names straight from historical documents. They reflect the real naming pattern from the time of Jesus and even more so than the writings of Josephus.

Discussion with Inspiring Philosophy- 4x1-Minute Cases

Below is a transcript on my discussion with Inspiring Philosophy on this topic.

ST

As part of my writing, I do one-minute cases from time to time. I was wondering if you'd be able to give us a quick case for each Gospel, whether it's 30 seconds or a minute, demonstrating it is an eyewitness account?

IP

Mark

Let's start with Mark, because Mark is the first one written. Well, Mark surprisingly tells the story from Peter's perspective in so many ways. Peter's often speaking on behalf of the group.

He's who Jesus is addressing. Things are told from his perspective in a lot of ways, like after Jesus's arrest, his story is told independently. And then at the end in Mark 16, it says, go tell the disciples and Peter.

So the church tradition is that Mark was writing down the preaching of Peter. And it's interesting that it's often told from Peter's perspective in very intricate ways that we don't see in the other Gospels. But this very much does seem to be the preaching of Peter.

And that would support the notion that Mark was using Peter as a source. Even Maurice Casey, who is an atheist, wrote a book called Aramaic Sources for the Gospel of Mark and said that Mark was getting his information from some Aramaic source and probably a member of the 12. Well, that likely would have been Peter if you combine it with the church tradition.

Matthew

Now, when we look at Matthew, people go, well, how could Matthew be an eyewitness if he was using Mark as a source? But scholars have noted, even Dale Allison has noted, that sometimes Matthew is more reliable than Mark. And it seems to be written by a Hebrew-speaking Jewish Christian who is really just enhancing the Gospel in multiple ways.

But also he is very much interested in monetary aspects, more so than the other Gospel aspects. He often gets the right names of coins in ways that other Gospel authors just sort of speak about coins generically. And he'll use very specific terms for coins.

And he's very interested in monetary policy. So we see a lot about money and debt in Matthew's Gospel more so. So that would support the notion that a tax collector wrote this because whoever wrote it was very much interested in and knowledgeable of monetary aspects.

Luke

Luke tells us he got his information from eyewitnesses. And then we see throughout his Acts of the Apostles, he keeps using these wee passages, sections where he claims to be travelling along with Paul. Well, throughout his Gospel, it's filled with Semitisms (eg. Aramaic linguistic feature).

But then when we get to the wee passages and the opening prologue of Luke, it has very few Semitisms in it. So that would tell us that this is some Gentile Christian who, when he's writing his own accounts in Acts, he's writing as a Greek Christian would. But when he's talking about Jesus, he's not using the same language and he's using a ton of Semitisms, which suggests he got his information from some Semitic speakers.

Also, he is very much interested in medical language, which the church tradition is that he was a doctor. So there's a lot more medical language that scholars like Luuk van de weghe have highlighted throughout his Gospel.

John

And then John is the most vivid of all the Gospels.

It has so many accurate details. And you just go through Craig Blomberg's book, The Historical Reliability of John's Gospel, you get fact after fact, after fact, after fact, confirming that what we have here is a very reliable Gospel.

Onomastic congruence (evidence from names)

And then when you take all four of the Gospels and Acts, Luuk van de Weghe and Jason Wilson did a study on the naming patterns in them and found that it's extremely reliable.

So if you look at the naming pattern in Josephus, it's got a 7% chance of matching the naming pattern from ancient Judea at the time. But the Gospels in their study scored an 86% chance of having an accurate naming pattern from the first century. That's something that you wouldn't get if you were writing fiction, because they also looked at like Apocrypha Gospels and fictional accounts.

And neither of those works, or none of those works were able to get accurate naming patterns from the first century. But Josephus and the Gospels could, which tells us it's very likely that whoever was writing these documents were getting their information from actual people that were in Palestine and actually did interact with Jesus and the disciples. So there's just a lot, and that's just the tip of the iceberg.

There's a lot of evidence for reliability and that the Gospels use eyewitness accounts.

ST

Sorry, with Josephus, did you say 70%?

IP

No, Josephus got 7%.

ST

Seven, yeah, right. I thought you might have said seven, but wow, that's very low. So that's the studies on onomastic congruence that you've done some videos on and also referred to in your Gospel series, right?

IP

Correct.

ST

Yep. And that would be building on the work of Bauckham, he did some work on that, I think a while back, looking at the names between 330 BC and 200 AD in Palestine with the bulk of the data coming from 50 BC to 135 AD. So that would be building on that database using more statistical means.

IP

Yeah, they build on Bauckham a lot and they corrected him in certain ways and they actually ran it through a goodness of fit test, so an actual mathematical model, which Bauckham never did. So this has really made this argument far more superior than whatever Bauckham put forward.

You can read more of our discussion here:

What this all means - Is the Jesus of the Gospels the Jesus of history?

If the Jesus of the Gospels is the Jesus of history, then the stories in the Gospels that changed the course of history can change the course of your life. Claiming to be divine (Mark 14:60-65), yet outcast and marginalised before coming back to life, the Jesus of the Gospels came to seek and save the lost (Luke 19:10) and to give His life as a ransom for many (Matt. 20:28). We have more on this in the links below.