The Crucifixion: 1-Minute Case On Evidence and Significance

Mockery. Shame. Disgust. History. Narratives. Fallenness. Identity. Restoration.

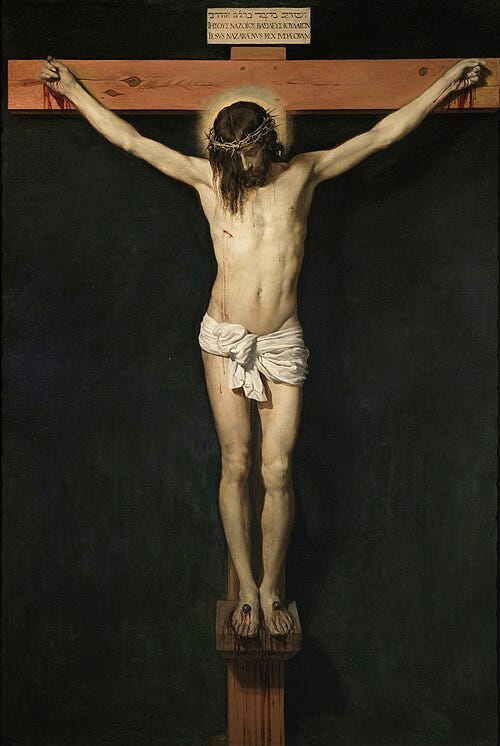

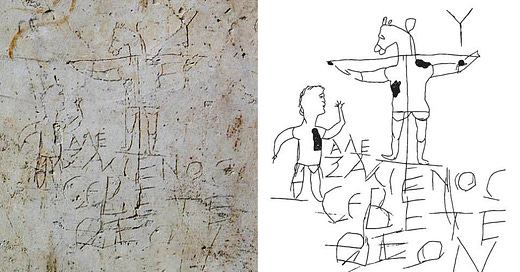

One of the earliest depictions of Jesus’ crucifixion is mocking a man who worships a crucified donkey as God. Yet, as time progressed Jesus’ crucifixion became a dominant theme in art, depicting Jesus as an exalted person who willingly made a sacrifice. What marked this change?

1. The crucifixion is a historical fact

Non-Christian scholars like Ludemann refer to it as “indisputable,” Ehrman “one of the most certain facts of history,” and Crossan “as certain as anything historical can ever be.”

Josephus (c. 37–100 AD) says Pilate “condemned (Jesus) to the cross” (Antiq. 18.3), Tacitus (c. 56–120 AD) that Christus “suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius” (Ann. 15.44), Mara Bar Serapion (c. 73 AD) alludes to the Jews “executing their wise king” (Letter to Son), the Talmud (2nd- 5th centuries) states “On the eve of Passover Yeshu was hanged (crucified)” (San. 43a), Lucian (c. 125–after 180 AD) purports Christians “worship the crucified sage” (Death of P.), Africanus (c. 160–240 AD) claims Thallus (c. 60 AD) in History tried to explain the darkness during Jesus’ death naturalistically.

This is not to mention the pre-Markan narrative in Mark 14-15 some scholars like Pesch and Casey date to the 30s or 40s AD, references from Paul (eg. 1 Cor. 1:23), Luke (23:46), 1 Peter 2:24, Hebrews 12:2, John (19:30) and Matthew (27:44). Let alone early church fathers like Clement of Rome (1 Cor.), Ignatius (Smyrn.) and Justin Martyr (1 Apol, 55).

2. Embarrassing history

Ancient Roman writers like Seneca and Cicero emphasised the utter disgrace, shame and humiliation associated with crucifixion. Following the Spartacus revolt in 73 BC, 6000 rebels were crucified along the Appian Way. Public humiliation. Nudity. Excruciating pain.

3. The story behind the history

Christ’s death reconciles our estranged hearts to God, bringing peace and healing despite our hostility (Col. 1:20). He fulfils the hilasterion—the mercy seat where purification from sin occurred in the temple (Rom. 3:25, Heb. 9:5). While sometimes translated “expiation” or “propitiation,” hilasterion echoes the Septuagint’s term for that sacred place of cleansing.

Jesus willingly lays down His life (John 10:18) and yields His spirit (Matt. 27:50). His crucifixion becomes the ultimate amartia—a sin offering, not merely sin—mirroring the sacrificial language of the Old Testament (2 Cor. 5:21).

This moment marks triumph over sin, death, and the demonic (1 Cor. 15:55; Col. 2:15; Matt. 20:28), a liberation we could never earn. No wonder the story doesn’t end here.

The Question

This crucified Messiah demands not just thought, but response. How will your sins be blotted out before God? Where will you look to victory, identity and deep inner healing? The question isn’t if He died—it’s if you’ll follow.

![The Alaxemenos Graffito, one of the earliest depictions of Jesus. The graffiti shows Jesus on a cross with a donkey's head, with the inscription "Alexamenos worships [his] god," apparently meant to insult The Alaxemenos Graffito, one of the earliest depictions of Jesus. The graffiti shows Jesus on a cross with a donkey's head, with the inscription "Alexamenos worships [his] god," apparently meant to insult](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!aYyY!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fefe0f857-1b57-4e13-8d94-cacc833c60e1_968x550.jpeg)